New Wave of Clergy Attacks Rekindles Fears of Christians Persecution, As U.S. Pressure Mounts

The abduction of another Catholic priest in Kaduna State has thrust Nigeria’s long-running crisis of violence against Christian communities back into national and international spotlight, renewing allegations of a “silent genocide” and amplifying calls for stronger state action.

Reverend Bobbi Paschal, Parish Priest of Saint Stephen Parish in Kushe Gugdu, Kagarko Local Government Area of Kaduna State, was allegedly seized from his residence in the early hours of Monday, November 17, 2025.

According to reports, armed men were said to have stormed the rectory, after overpowering the local vigilantes, and abducted the priest to an unknown location. His captors are widely believed to be part of the network of extremist groups and bandit formations that have terrorised rural communities in Kaduna State for more than a decade.

His kidnapping came barely days after another major security incident in the Northeast; an ambush on Brigadier General Mohammed Samaila Uba, a commander of a Joint Security Task- force in Borno State. Boko Haram and ISWAP fighters have circulated images of the attack on social media, affirming another stark reminder that both religious leaders and state security officials remain prime targets in Nigeria’s unstable security landscape.

This affirms more than a decade of targeted violence against the Clergies and other Nigerians.

Christian clerics; priests, pastors, seminarians, and their families have endured a persistent pattern of targeted violence, particularly in Kaduna, Plateau, Taraba, and parts of Benue. From church invasions to highway kidnappings, religious leaders have become symbolic targets in ways that security analysts argue are both strategic and deeply ideological.

Extremist organisations use clergy abductions to fracture local communities, weaken public morale, and demonstrate the state’s inability to protect its moral authorities. In many rural areas, the killing or kidnapping of a pastor or priest has become disturbingly normalised.

Elsewhere in Southern Nigeria, priests among other beings are the vulnerable.

A Catholic priest attached to my Parish at St. Pius X Parish, Ikot Abasi Akpan and Solid Rock Kingdom Church founder in Akwa Ibom; medical doctors, businessmen, teachers had been victims of this menacing venture.

“For years, Nigerians have buried one priest after another,” one community leader in Southern Kaduna said noting that, “People are tired of living in fear, and also tired of government statements that lead nowhere”.

Despite repeated pledges by successive administrations to improve intelligence gathering and dismantle terror cells, communities say government responses usually lag behind the crisis, as ransoms continue to be paid and families continue to grieve, while extremist violence continues to spread into previously unaffected regions.

Security experts warn that, the lack of swift investigations and successful prosecutions have emboldened attackers to continue. “When terrorists see no consequences, the violence escalates,” a retired military officer said.

The resurgence of Christians attacks is also echoing beyond Nigeria’s borders, as international attention re-ignites the debates.

U.S. President Donald Trump, during his first tenure frequently criticised Nigeria under Muhammadu Buhari for alleged religious persecution. Again, the country is being cited by activist groups who argue that Nigeria must face renewed diplomatic pressure over perceived genocide or killings of Christians.

Trump’s earlier threats of sanctions and public rebukes briefly shone a global spotlight on faith-based violence in the country. Yet the long-term effects of that pressure remain limited, as insecurity persists and local communities continue to suffer.

Some Christian advocacy groups insist the, time has come for international actors and world leaders to speak up again, while others argue that external pressure cannot replace domestic political will.

The latest attacks have re-ignited heated debate over whether the ongoing violence in some Northern States of Nigeria constitutes a “Christian genocide.”

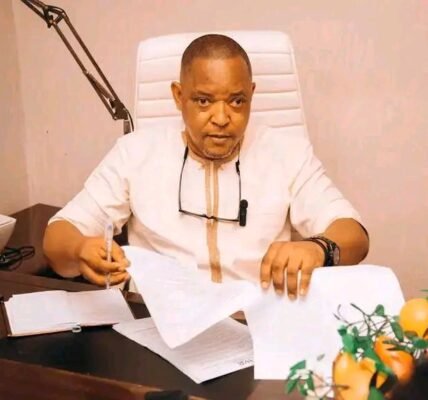

However, activists like Rev. Ezekiel Dachomo, a vocal critic of violence against Christians communities in Nigeria’s Middle Belt particularly, Plateau State, Benue, Taraba etc accused the governments and security agencies of complicity or failing to protect Christians.

Dachomo, who is the Chairman, Church of Christ in Nations (COCIN), has repeatedly warned that, the targeted killings of clergy and attacks on rural Christian communities are systematic, deliberate, and should be recognised as Christians genocide.

Though Muslims, traditional rulers, and other civilians have also suffered devastating attacks, but the consistent targeting of Christian leaders has become a flashpoint for public anger.

“We cannot keep quiet anymore,” a parishioner in Kagarko declared. “No priest is safe. No pastor is safe. If the government cannot protect us, who will?”

This is an indication of a nation at a crossroads, Mr. Kagarko declared. For many Nigerians, the question is no longer whether the world is watching, but whether the Nigerian state will finally match community resilience with effective protection.

As the search for Reverend Bobbi Paschal continues, faith leaders and civil society organisations are urging the government to treat the abduction as a national emergency rather than another entry in the country’s long list of tragedies.

Meanwhile, the federal government of Nigeria has rejected the idea of Christians genocide. Foreign Affairs Minister, Yusuf Tuggar, strongly denied that the government is complicit in any state-backed religious persecution. He said such persecution “is impossible at any level of government under Nigeria’s constitutional system.

To underline his claim, the Minister flaunted a document titled “Nigeria’s Constitutional Commitment to Religious Freedom and Rule of Law”, indicating religious freedom is enshrined and guaranteed in Nigeria’s constitution.

Also, the Minister of Information, Mohammed Idris Malagi did not minced words when he emphasized that, violence targets all faiths. He argued that, many of the violent attacks in Nigeria do not discriminate by religion; Christians and Muslims are both victims.

Hon. Malagi also accredited the security complexities in the country to Boko Haram, banditry, resource conflict saying, framing it purely as “Christian genocide” is overly simplistic, and cautioned against “efforts to destabilize” Nigeria via such narratives.

Until concrete action replaces rhetorical condemnations, many fear that the cries of victims will continue to be met with silence.